By Elham Ali

In recent months, the U.S. Digital Response health program has partnered with a number of public health offices, governments, and community organizations to implement digital communications tools and carefully crafted messaging designed to reach and resonate with a diverse range of communities. USDR’s partners share a goal of establishing COVID-19 vaccinations as a social norm that is both acceptable and regarded as collectively beneficial. Examining their communications through an equity lens is essential to meeting this goal.

Here, we’ve outlined lessons learned to help communicators achieve equity in their campaigns to vaccinate the public. Additionally, USDR has compiled a communications toolkit that aggregates our design and research work from the past months and provides actionable steps, checklists, and downloadable materials to help evaluate and make design and content changes to your existing materials.

Our advice for building equity into public health communications rests on a health equity framework that examines four pillars:

- Acknowledge the systems of power that promote social, economic, and environmental equity

- Build long-term local grassroots relationships and networks

- Weave in equity as part of design and research infrastructure

- Use equity-focused data to inform on individual and community behavior

Below is a short explanation of each principle and examples from our experiences to illustrate their value.

Acknowledge the systems of power

The relationship of a design and research participant and the sponsors funding that research is skewed. Sponsor organizations hold essentially all of the power: Decision-making power, structural power, organizational power, and in most cases, monetary power. But when they embark on a mission to hear and understand the voices of their users, they’re symbolically sharing a small portion of that power with their community.

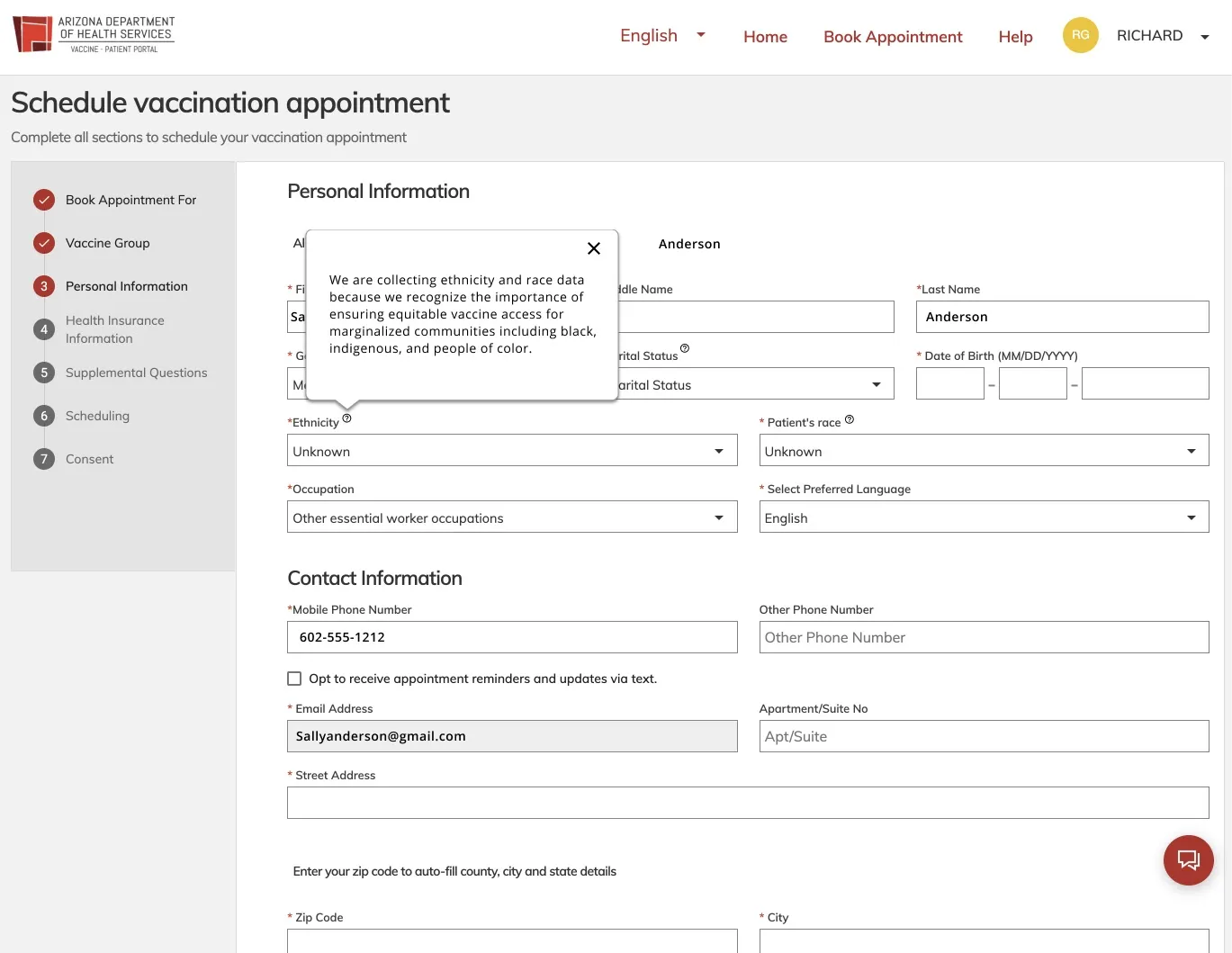

We recognized that equitable communication starts with our own team shifting the scales of power back to the participants who were collaborating with us. We responded by giving residents that power back. For example, we conducted bilingual usability testing for a patient vaccine portal with the State of Arizona Department of Health Services. Our research insights led us to:

- Reduce a person’s anxiety by adding documentation support to empower them to collect all necessary data before booking an appointment

- Add an FAQ to respond to critical use cases for undocumented workers with different forms of ID, cost of vaccine, and info for parents and children

- Design signifiers like tooltips to explain the important of collecting ethnicity and gender data

- Provide gender inclusive categories and expansive ethnicities that are beyond the census tract scope

- Address fears on insurance requirements and impact on immigration with microcopy

Build long-term local grassroots relationships and networks

Our primary and secondary research shows that immigrants and their families don’t necessarily form relationships within governments. They have their own communities and networks outside of government authority.

We recognized the importance of implementing a bottom up approach with a hyperlocal focus on community-based organizations (CBOs) and decentralizing vaccination response back to the community. We will not be able to overcome the legacy of mistrust of our government partners and medical institutions overnight, but engaging these community leaders is an essential first step from the start.

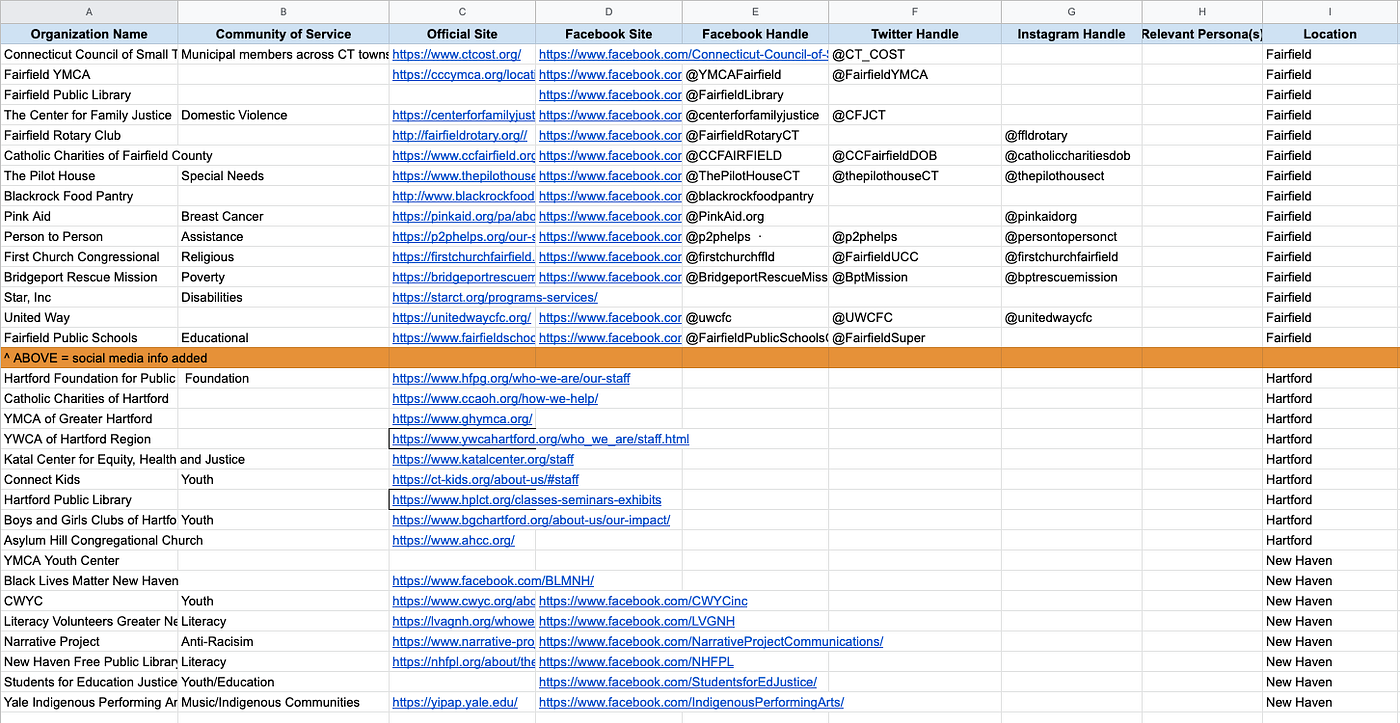

As such, we aimed to create digital partnerships that are liberating for all in the process. For example, we worked with the State of Connecticut to audit its social media for COVID-19 communication. We aggregated a list of reputable local organizations into a spreadsheet — which includes some social media handles to help with outreach efforts. This approach is people centric, as opposed to platform centric social media. It builds digital partnerships by tagging key communities to reach marginalized and historically low-vaccinated communities.

Other examples of strategic partnerships include the work of the KINA (TOGETHER), a series of projects headed by the University of Minnesota designing and developing in partnership with local Native American communities. The project’s underlying belief is rooted in the idea that the communities we serve know what is most helpful for their members and need to be equal partners in what we offer. Pictured below is a comic flyer for youth on COVID-19 preventative practices.

Weave equity as part of design and research infrastructure

In our early concept testing sessions for social media messages that resonate with BIPOC participants, we learned that our sessions are spaces for healing. They gave our participants an opportunity to speak about their trauma outside of their social circles. We realized the impact that trauma has had on individuals and their interactions with government systems.

“My wife really tried. She was like a hawk waiting on every appointment she can book for herself. I wanted to help her but I felt hopeless. She eventually stopped trying to look and gave up. People lose motivation.”

— A participant in a concept testing session

Recognizing these signs of trauma, we provided our participants with resources for questions that they had in a way that resists retraumatization. Questions that came up included variants, vaccinating kids, and life after the pandemic.

Other government partners also responded to reducing those structural barriers in their compensation models: pairing research with WIC and SNAP benefits. We provided feedback to government partners to create weekly user research panels to cultivate relationships with their communities.

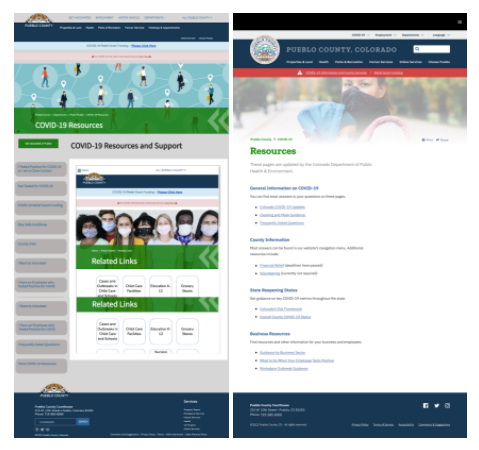

Additionally, we focus on challenging assumptions on how physiological responses can be driven by other spheres of influence and how accessibility interventions can maximize and support the resilience of physiological functions and abilities after exposure. Our work with Pueblo County, CO allowed us to work on common accessibility challenges such as:

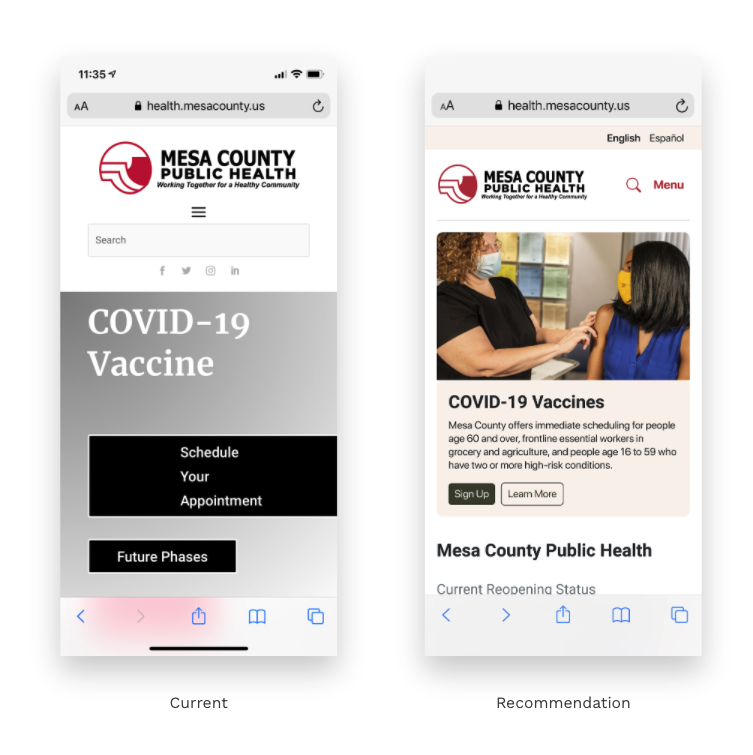

- Writing at a 3rd grade reading level to accommodate various digital and health literacy levels. Others navigate life through proxies such as people with dementia who rely on caregivers, and children who make health decisions on behalf of their undocumented parents

- Prioritizing mobile designs to accommodate for people with motor functioning diseases like Parkinsons where they need larger focal points in mobile designs

- Positioning call-to-action above the fold to account for elderly people with shorter working memories than the general population

Use equity-focused data to inform on individual and community behavior

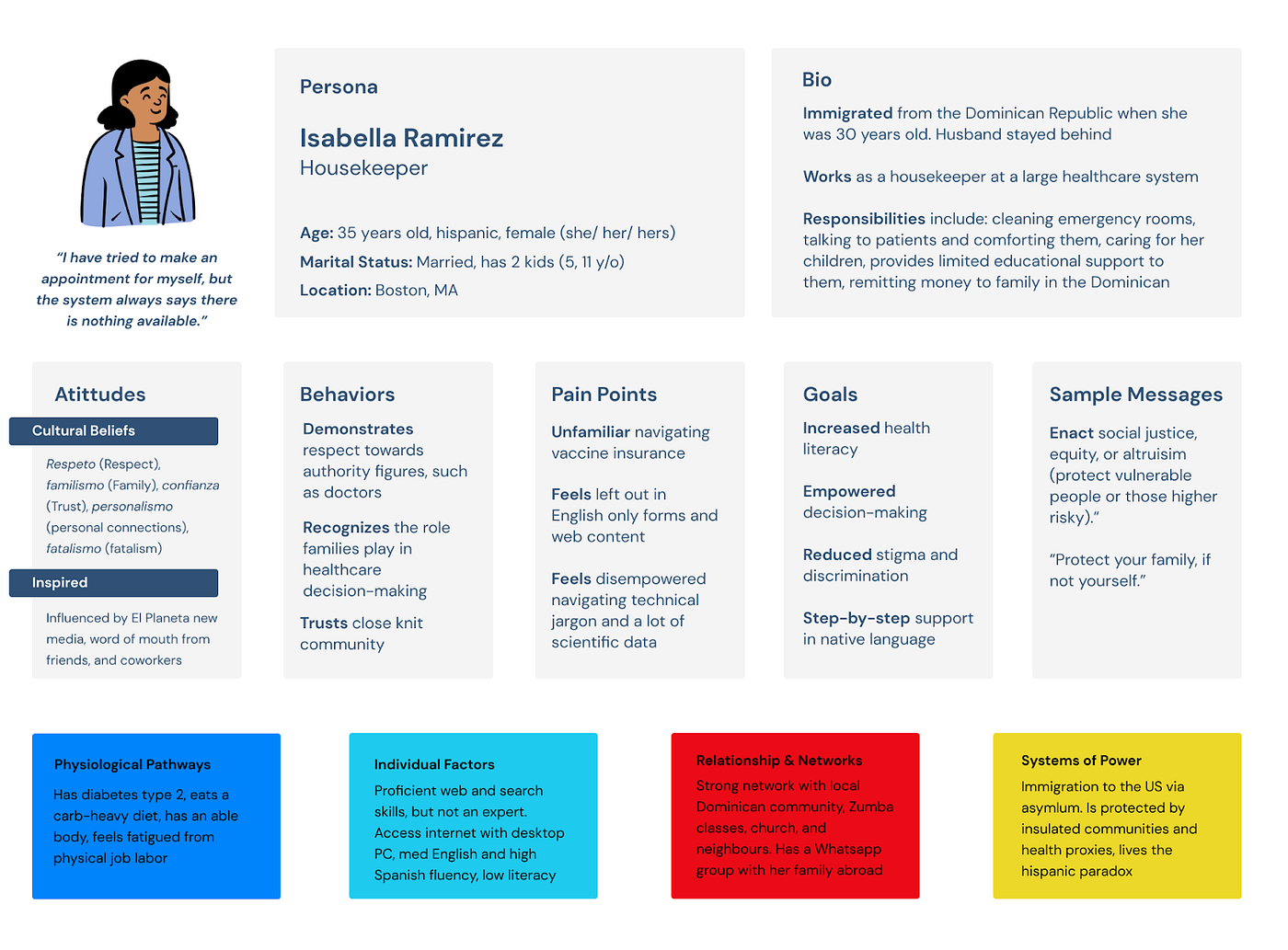

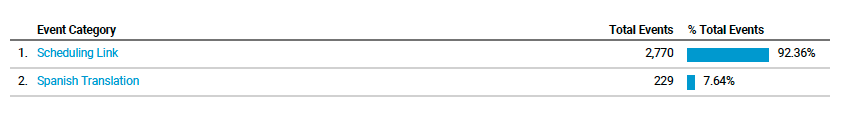

Individual factors such as attitudes, skills, and behaviors impact a person’s personal and community’s health. Working with our partners, such as Mesa County, CO, we identify equity data that supports equitable convenience, confidence, and social norming. Multilingual translated and transcreated communication material were key to align to culturally and linguistically responsive materials for accurate and accessible vaccination information.

This led us to add bilingual translations such as Spanish. In this example, we make both accessing English and Spanish translation and booking a vaccine appointment an easy and convenient choice, which is key to increase uptake.

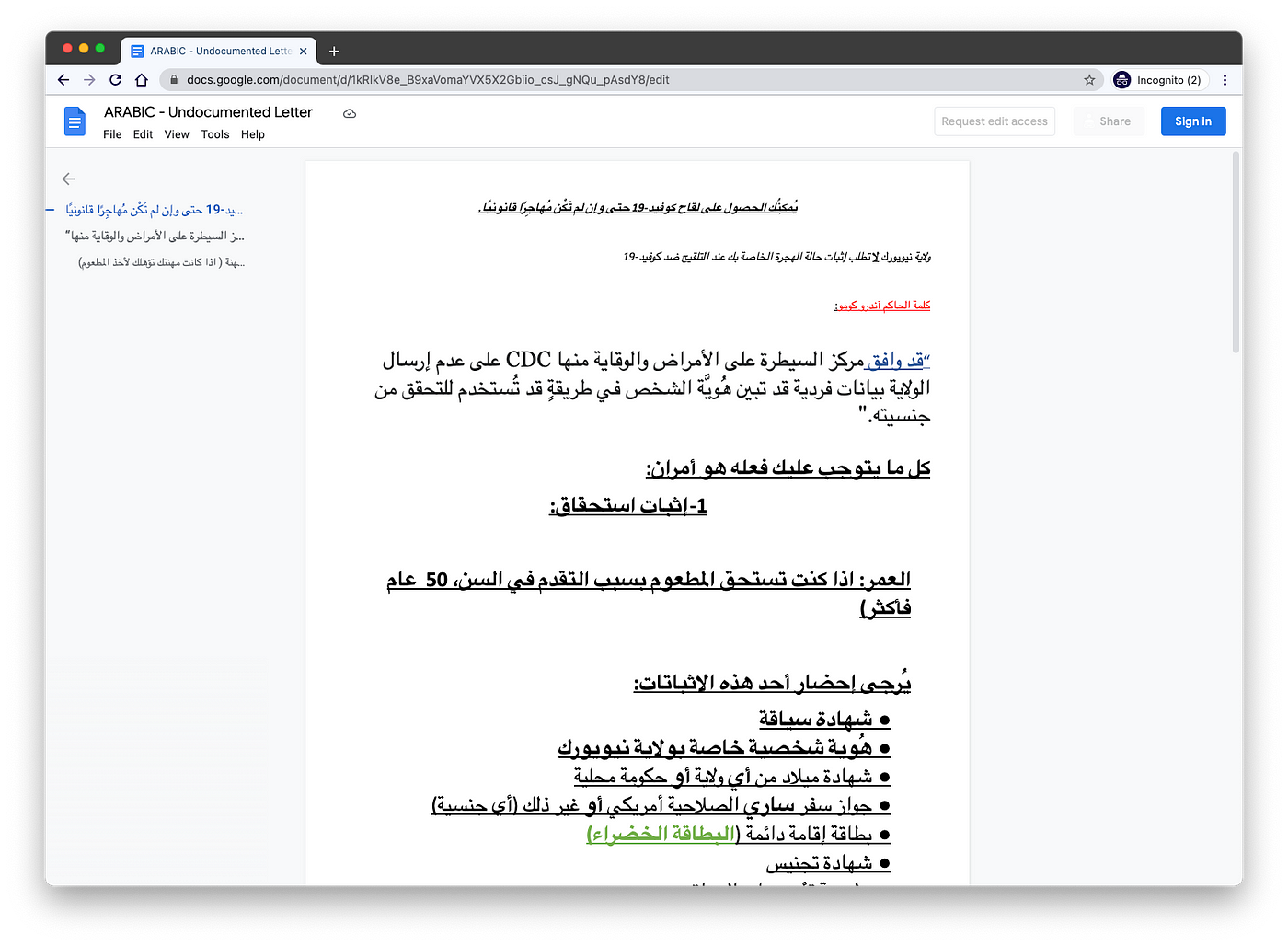

Other examples are transcreated materials such as the work of Epicenter NYC, which published a public folder that provides multilingual occupation letter templates and undocumented immigration letters for download. It was inspired by workers at outlets like GrubHub and Uber having access to such proof of occupation on their phones.

We know that content managers and developers of digital health information tools are faced with the difficult task of imagining what your end-users will find understandable and actionable. Although there are a number of strategies from personas to use cases to make your content more user-friendly, many do not account for the everyday changes in residents’ attitudes, behaviors, and wayfinding efforts related to vaccines and testing.

USDR has a pro bono team of experts ready to help you close the gap that exists between writers and developers and their end-users and to help create more accessible and equitable consumer-centric digital tools that can ease the burden of navigating complex digital health information. Fill out this brief intake form to request support from USDR and we’ll be in touch within 24 hours.